Few subjects trigger stronger feelings than race, ethnicity and religion. While related, these three anthropological concepts have distinct meanings and are not as readily interchangeable as many ideologues may prefer. Broadly speaking race refers to our genetic inheritance, ethnicity to our cultural background and religion to our belief system. While we cannot change our genetic inheritance or choose our upbringing and the community of our early years, we may, at least in liberal secular societies, adapt to new cultural influences and choose our faith later in life. Put another way, while race is a matter of nature alone and religion is wholly nurture, ethnicity is at the crossroads between society and biology.

People tend to mate with other members of the same ethnic group who share the same core cultural traits and moral codes. At least this was the norm before the current era of easy long distance transport and international commuting. As a result in-group racial diversity wanes over successive generations. While racial differences are a product of gradual genetic adaptations over extended periods of separate evolution, ethnic allegiances are much more fluid. Historically outlier tribes have regularly merged with more successful communities to form new larger national groups. However, full integration is often hampered by divergent racial profiles within different social classes of a large ethnic group. In the age of colonisation, many new nations were formed this way. Although Brazil and the United States of America have distinctive national cultures, social classes still reflect the racially segregated reality of the slave trade. Both countries are products of relatively recent European settlement of what we once called the New World and supplanted well-established indigenous nations.

In Europe and much of Asia, modern culturally homogeneous nation states evolved from smaller organisational units such as fiefdoms, principalities or city states. Over time larger nations helped accelerate the process of ethnic integration, usually favouring the culture of the more influential urban professional classes. Regional differences remained strong in much of Europe until the advent of compulsory schooling that spread literacy in the standard national language. Nonetheless the concepts of nationhood and ethnicity are usually closely related. The former has to be more inclusive of variant and minority identities, but neither necessarily matches current geopolitical boundaries, e.g. the Hungarian nation may be either the citizens of the geopolitical entity of Hungary with internationally agreed borders, whether or not they consider themselves Hungarian, or the aggregation of settled Hungarian-speaking communities spread over a wider area in parts of neighbouring Slovakia, Ukraine, Vojvoidina and Transylvania. To confuse matters further, we may refer to larger groupings of people with shared racial and cultural characteristics as ethnoracial groups, where broad ethnic categories correlate strongly with genetics, but often to the exclusion of minorities within cultural communities that do not share these traits. The last UK census asked broad-brush questions about racial and ethnic identity with categories such as white British (in England and Wales), Scottish (in Scotland only), Afro-Caribbean, Black African, Indian, Pakistani and East Asian. These categories, reflecting migratory and settlement patterns in Britain since the 1950s, are of questionable value to anthropologists. Historians seldom hesitate to distinguish native Australians from subsequent settlers who arrived from Europe, and later from Asia, Africa and elsewhere. A native Australian is someone who can trace their ancestors to the land Down Under before European colonisation displaced them from the continent’s most fertile regions. Yet terms like native British have all of a sudden become problematic as it excludes everyone who descends from more recent migratory waves and more poignantly implies a significant break from the recent past.

One of the greatest ironies of recent history is that the same forces of first mercantile imperialism and later global corporatism that led to the almost complete ethnic cleansing of Australia in 18th and 19th centuries are now having similar effects in many towns and cities across Western Europe, as the autochthonous peoples become an ethnic minority in what they once believed was their country. In both cases we see a sudden break in cultural continuity that disproportionally impacts people with the least economic means.

The world’s leading religions have long transcended both racial and national boundaries, although religion is often a key ethnic identifier, e.g. Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland or Croats and Serbs in the former Yugoslavia. Christianity spread from the Middle East among largely Semitic peoples to Europe and West Asia and as far as India Sri Lanka long before the expansion of European empires. Likewise Islam expanded to Indonesia in the east, to Morocco in the west, to Zanzibar in the south and Bosnia to the north long before the current era of mass migration. While some religions may be more common among some ethnoracial groups, e.g. Hinduism has spread mainly in the Indian subcontinent, they are belief systems that govern morality and socialisation.

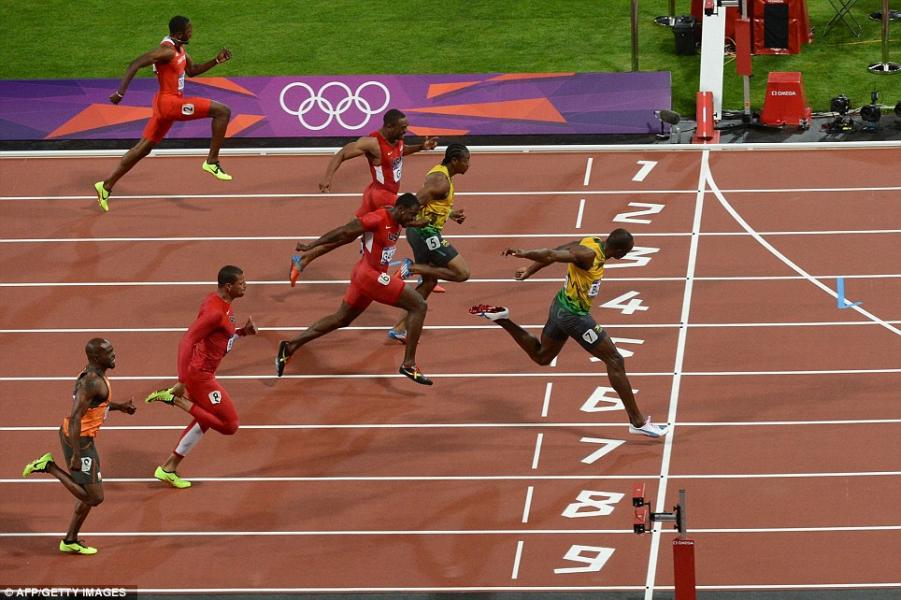

Some would prefer to deny race exists at all, thus confusing ethnicity, relying on strong cultural bonds which anyone could adopt with enough willpower, with genetic traits beyond our control. While traditional groupings like Sub-Saharan African, Caucasian or East Asian oversimplify our genetic ancestry to fit broad criteria such as geography and complexion, no serious anthropologist can deny biological differences within the human species on ideological grounds. Science has to distance itself from politics. Sometimes small adaptations that evolved gradually over thousands of years of natural selection in distinctive habitats can lead to big differences to performance in competitive pursuits and occupations. It’s not a coincidence that the world’s fastest sprinters are overwhelmingly of Caribbean African descent. White Europeans and North Americans only faired better in the first half of the 20th century because they had access to better training facilities, but with an even playing field small evolutionary adaptations within subsets of the same species matter. The fastest white European is Christophe Lemaitre, who only broke the 10 second barrier for the 100 metres dash in 2010, compared to Usain Bolt’s 9.58 seconds. That difference may seem small, but would leave the Frenchman around 4 metres behind the world record breaker. This begs the question whether genetic differences could impact intellectual performance. However, to muddy the waters analytical intelligence may vary greatly within members of the same ethno-racial group. A complex society needs both conscientious workers able to follow instructions in a socially cohesive way and more creative innovators with strong problem-solving and critical thinking skills, but often lacking in empathy. Nonetheless it is not beyond the realms of scientific probability that if tens of thousands of years of separate evolution can lead to differences in physical pursuits such as running or swimming, adaptation to new hostile environments, requiring the development of new technologies, could lead to neurological differences among subsets of the human population. Is it a mere coincidence that East Asians are overrepresented among hardcore software developers? These are big and controversial questions that only objective and dispassionate science can answer.