Before sometime around 1990, while I lived abroad in Italy, most large institutions and the establishment media in the North West of Europe liked to refer a place called Britain and proudly used adjectives like British to include England, Wales, Scotland and, by loose extension, Northern Ireland too. Outside the UK confusion reigns supreme as England, Great Britain and United Kingdom are often used interchangeably. Indeed, many English people often struggle to recall the correct name for their country. This may sometimes lead to false positives with regular references to British Law, when as a result to the 1707 Act of the Union, Scotland has always retained a separate legal system and Northern Ireland’s juridical framework has its roots in Irish common law.

If you want to be pedantic, then the island that comprises England, Wales and Scotland is Great Britain, while Britain alone may refer to just England and Wales and the United Kingdom includes Northern Ireland too.

Scotland and Wales have never lost their distinctive identities, but over the generations, and especially since the industrial revolution, there had been so much intermarriage and movement among the peoples of the home nations, that Scottish and Welsh separatism seldom gained more 25% of the vote. Welsh nationalism focused mainly on protecting the Welsh language after centuries of suppression, while Scottish nationalism only really gained momentum after the discovery of vast oil reserves in the North Sea in the 1960s. If anything Scotland has long been overrepresented within the Union, relative to its population, which has declined from around 1/9 of the UK total circa 1900 to less than 1/11 today (although still rising in absolute terms) with more than its fair share of prime ministers, entrepreneurs and inventors.

British identity grew in the Victorian era on the back of the industrial revolution and expansion of the British empire over a quarter of the Earth’s landmass. Without Scotland and Ireland’s plentiful natural resources and critical mass of engineers, Great Britain may never have gained such a large competitive edge over its main rivals, France and Spain, in its quest to colonise North America and dominate world trade. Although Britain’s relative importance declined with the emergence of Germany as the main European powerhouse and the United States as the world’s dominant economic superpower at the turn of the 20th century, British identity remained strong through two calamitous world wars and the Great Depression. Britain emerged from the Second World War very much as a junior partner of the United States with an oversized empire it could no longer afford to maintain, but it had at least escaped the worst ravages of Nazi occupation and widespread ethnic cleansing. The peoples of England, Wales and Scotland were still proud to identify with Britishness as the country transitioned to a new role as a medium-sized Western European power on a par with France, West Germany and Japan and subservient only to the USA. The old empire had become a motley collection of new nation states. Some, like Canada and Australia, retained very strong cultural affiliation, but soon integrated much more with the booming North American or East Asian economies. Others, like India and most of British Africa, retained the English language as a commercial and scientific lingua franca, but sought new alliances. The continuing importance of global English bears little relation to the current status of the UK. It is a legacy of Britain’s Mercantile hegemony in the 19th century and the USA’s economic and cultural dominance of the 20th century.

An irony of history is that despite losing two world wars and much of its eastern territories, West Germany regained its role as the motor of the European economy. Having your main industrial areas carpet-bombed may lead to temporary loss of human life and manufacturing capacity, but it certainly facilitates productivity-boosting modernisation. By the 1970s Britain was the sick man of Europe, plagued by industrial strife and inefficient infrastructure. Much of British industry either outsourced production overseas or gave up entirely, refocusing instead on the growing service sector. To add insult to injury, in the mid 1980s the Italian economy briefly overtook the UK’s. Indeed despite recent economic decline, Northern Italy remains much more affluent than most of the UK with larger houses and higher car ownership. More recently India, Russia and Brazil have overtaken the UK’s GDP once adjusted for purchasing power parity and it’s only a matter of time before they do so in absolute terms too.

When did the new generation of UK citizens stop identifying as British?

It all depends what you mean by British? As a loose synonym of English, then most people in provincial England are probably happy to call themselves either. But only English is a true ethnic marker close to people’s heart. Naturalised UK citizens, especially from Commonwealth countries, often prefer hyphenated British identities as being more inclusive. The more integrated someone with an immigrant background is, the more likely they are to identify as English, Scottish or Welsh. I used to think that the millions of Britons with mixed English, Scottish and Welsh heritage would more readily identify as British, but outside the London area, this no longer appears to be the case. Your childhood friends, especially in your core school years, tend to instil ethnic identity in you more than anything else. Just as the Scots are reasserting their rebranded Scottish identity, even if their parents come from England, Italy or Poland, so too are the working classes in provincial England once again identifying first and foremost as English.

In the late 1990s I noticed a shift in the mainstream media, especially in one of the last institutions to incorporate British in its name (the BBC). All of a sudden presenters and politicians started to avoid references to Britain and Britishness in favour of the Yookay, the United Kingdom, just “this country” or weird concoctions like England and Wales or England, Wales and Scotland if one or more parts of the UK were excluded. Tony Blair’s New Labour government seemed happy to acquiesce to demands for greater devolution in Scotland and Wales, although support for the Welsh Assembly only won by the narrowest of majorities in the 1997 referendums on the matter. As Scotland and Wales had suffered much from the industrial decline of the 1970s and 80s, devolution seemed like a long overdue constitutional reform. In the early years Labour dominated both the Welsh Assembly and the Scottish parliament but had to seek an alliance with the Liberal Democrats due to the new mixed proportional representation voting system. For a while the Scottish National Party’s failed to make any significant headway. As recently as 2005 the SNP gained just 17.7% of Scottish votes in the UK general election after polling a disappointing 20.9% in the 2003 Scottish Parliamentary Elections, despite the unpopularity of Blair’s Iraqi misadventure. Four years later the SNP under Alex Salmond managed to pip Labour at the post winning 31% against 29.2% and just 1 more seat. The SNP formed its first minority government. Yet in the 2010 general election the Scots bucked the national trend with Labour gaining 42% of the vote, possibly because Gordon Brown remained popular north of the border, and the SNP just 19.9%. A year later the vote shares of Scotland’s two main parties were almost reversed in the 2011 elections for the Scottish Parliament, giving the SNP a working majority and paving the way to the 2014 referendum on Scottish Independence. Few observers would have predicted that in just 10 short years support for Scottish separatism could rise from a rump of 20% to just shy of 45%. The big question is why David Cameron’s coalition government so willingly acquiesced to the SNP’s demands

Mood Change

Traditionally the main institutions of successful nation states tend to resist separatism. We may be accustomed to the acrimonious breakup of unstable federations like the former Yugoslavia or the more amicable divorce of Czechoslovakia, but many have long suspected foreign intervention in their demise. When the levers of political and economic power move from compact nation states to supranational bodies like the European Union or NATO, the business classes shift their allegiance from their current national entity to the remote organisations best able to protect their commercial interests. In the era of international commuting, outsourcing and globalised supply chains, nation states appear to growing sections of the professional classes as anachronisms of the 19th century, discredited by the excesses of fascism and national socialism. If a country the size of Italy has limited operational autonomy, constrained militarily by NATO and economically by the IMF and the EU, what chance does a country the size of Slovakia, Croatia, Latvia or indeed Scotland have? Despite the much-maligned project fear during the Scottish independence referendum, the main arguments hinged on social security, oil revenues, currency, Trident nuclear warheads based in Faslane and Scottish jobs dependent on UK military contracts. Big businesses, while preferring easy access to the nearby English market, seemed almost indifferent. Tesco does not really care whether Scotland is nominally in some abstract entity called the UK as long as it can continue to bribe local councils to expand its retail empire, which now stretches as far as Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic and Thailand. The main reason the British Civil Service wanted to avert Scottish independence was the country’s tight integration into the British armed forces and, more importantly, NATO, but the SNP ditched its earlier opposition to NATO in 2012. Until recently the United States relied on the UK as its most loyal ally in its various military endeavours around the globe, but with shifting global alliances Uncle Sam is suffering from battle fatigue. The failure to overthrow the Syrian government and the rapid rise in China’s military budget and soft power have led military lobbyists to seek new vehicles for their nation-building operations. Recent US-led wars have done little to project American power, something much better accomplished by US-based tech giants. If anything, the USA’s military adventurism has weakened the country’s soft power, while the main hubs of technical innovation are moving away from California and elsewhere in the United States to the Far East, China, Russia and Europe. We should watch not so much the sales revenues of tech behemoths, but the concentration of talented engineers able to drive future innovation. Gone are the days when the best Chinese, Russian, Korean or Japanese engineers would be snapped up by American multinationals. Today, they often have better opportunities in their home countries and thanks to the wonders of modern telecommunications can collaborate with others around the world without having to emigrate. When the CEOs of American IT enterprises like Amazon, Facebook, Google, Apple and Microsoft are happy to lambast the current resident of the White House and seem more concerned with adhering to the edicts of the Chinese government than training young American software engineers, it must be crystal clear that they owe no special allegiance to their fellow Americans.

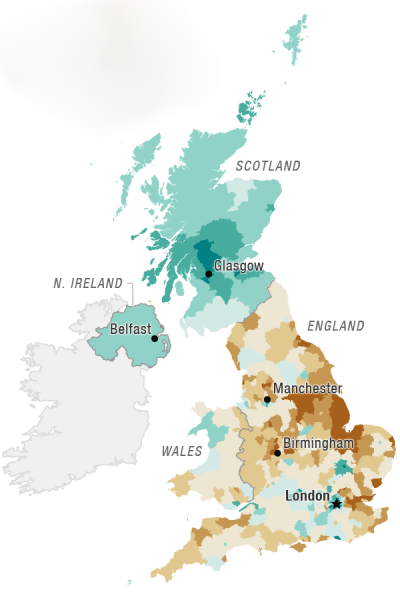

The Brexit Delusion seen from postmodern Scotland

Some believe the outcome of the 2016 referendum on the UK membership of EU marked a protest against the excesses of globalism and the disenfranchisement of the native working classes. Yet for all the bluster about taking back control and national self-determination, the United Kingdom appears less united than at any time since World War Two in the terms of social class, national identity and outlook on life. There are many good democratic reasons to advocate the transfer of power from remote superstates to viable nation states, but while a clear majority in the English provinces and in most of Wales voted to leave the EU, Scotland, Northern Ireland and inner city areas of England voted to remain. Two groups in particular opposed any attempts to restore national sovereignty, the affluent professional classes, especially in academia, and Britons with a recent immigrant background. The results in Scotland would have been very different if the SNP had opposed continued EU membership as they did the 1975 referendum. Many Scots voted to stay in the EU because they believed it made Scottish independence easier if the whole of the Former United Kingdom (FUK?) remained deeply embedded in the EU facilitating seamless trade and movement of people.

Let me suggest they were wrong for two simple reasons. First the Brexit saga has provided Nicola Sturgeon with a pretext to call another referendum on Scottish separatism. Second joining the EU as a separate member state would make Scotland a net contributor but without any subsidies from the UK government. So unless crude oil prices return to the heady heights of $120 a barrel, the SNP will be forced to drastically slash public services and welfare spending, especially as all new member states have to join the ERM and prepare to adopt the Euro. No pragmatic Scot could contemplate such socially divisive policies that could turn Scotland into a wetter and windier version of Greece under the now disgraced Syriza government (who promised to reverse EU-enforced austerity before agreeing to another loan requiring even greater cutbacks than anticipated). While many English workers have bought into the illusion of a strong and independent UK outside the EU, the Scottish working class have been sold a European pipedream that reflects the widespread middle-class affluence of 1990s Germany much more than the grim reality of Macron’s regime unable to contain open revolt from his country’s yellow vests movement.

The SNP’s love for identity politics and mass migration have set the party’s leadership on a collision course with their supporters who overwhelmingly want Scotland to be more Scottish in the traditional sense and less like the multicultural chaos they see in England’s metropolises. It appears the SNP leadership would be quite happy for Glasgow and Edinburgh to emulate London and Birmingham, while many of their supporters would much prefer the Norwegian model. Scottish nationalists and Northern Irish Republicans have been co-opted into the virtue-signalling no-borders movement. Their leaders not only oppose traditional family values, they want to redefine Scottishness or Irishness to mean temporary loyalty to your current jurisdiction rather than longstanding family ties or full cultural assimilation.

Over the last decade Scotland’s main cities have belatedly succumbed to the lure of global harmonisation, with segregated transient communities, gentrification of inner city neighbourhoods and sky-rocketing property prices in the wee nation’s capital. The SNP’s priorities have at best addressed short-term populist concerns, e.g. removing bridge tolls and offering free prescriptions, and at worst transferred more power to a centralised police force and invasive social services, especially the notorious named person act.

Most disturbingly the SNP’s education policies have significantly lowered standards, widening the gulf between the offspring of Scotland’s professional classes who can either provide an intellectually stimulating home environment or afford private tuition and the rest whose stressed parents struggle to deal with precarious employment and unstable relationships. The SNP may champion Scotland’s integration with the rest of Europe, but it’s made foreign languages optional guiding underperforming students to easier subjects. You might imagine that Scotland’s love affair with the games industry might have inspired a new generation of budding programmers. Alas tech companies struggle to find local whiz kids for mission-critical software development roles. The main advantage of moving an IT business from London to Scotland is not the availability of local talent, but lower property prices and smaller social extremes. If you have to import your best developers from Poland, Ukraine or India, then London, once a magnet for the best and brightest professionals, has no inherent advantage. A small country dependent not only on international trade, but also on imported human resources only has limited leeway to fine-tune its fiscal regime and employment laws to attract greater inward investment. The Irish government may have tempted Google and Twitter to set up their European HQs in its capital city, but the multinationals hired mainly non-Irish staff driving up property prices while a growing number of born and bred Dubliners are homeless. Under its new Taoiseach, Eire (more commonly known as Republic of Ireland) is currently undergoing its fastest rate of cultural transformation since it gained independence in 1920. Irish journalist, Gemma O’Doherty, has gone as far as to describe the government’s Project Ireland 2040 initiative as state-sanctioned ethnic cleansing, aiming to add 25% to the existing population while the country’s best and brightest continue to emigrate. The leaderships of Sinn Fein and the SNP may appeal to anti-British nationalist sentiment, but advocate socially engineered post-national identities for their respective fiefdoms.

The post-national Alliance

One photograph captures more succinctly than any others the duplicity of politicians we once believed had some principles, the spectre of Nicola Sturgeon hugging Alastair Campbell. I remember seeing Nicola speak at a small demonstration in Glasgow against the UK’s enthusiastic participation in the bombing of Serbia and Kosovo back in 1999, a courageous stance that involved challenging the bias and disinformation of much of the mainstream media. The SNP also opposed the 2003 invasion of Iraq, but fast forward to the current year and the same SNP has shifted its focus from opposing military adventurism and making the case for full fiscal autonomy to supporting full integration with the European superstate with its own plans for a unified military command and fiscal harmonisation. Rather than being deployed in conflict zones as British soldiers under the auspices of NATO, Scotland’s future military personnel could well serve in places as diverse as Ukraine, Mali or France as part of the new European Defence Force. Over the decades many high profile politicians as diverse as Bill Clinton and François Hollande have built their political reputations on opposition to imperialist wars, only to fall into line once in power. So what do the likes of Tony Blair’s former spin doctor, Alastair Campbell, and Nicola Sturgeon really care about? Their appeals to Britishness, Scottishness or working class solidarity have only ever been ploys to win electoral support. Both have failed their core electorates dismally, much preferring global grandstanding over local solutions. Alastair Campbell may have strategically supported US-led military interventions and nominally opposed Scottish independence, but that’s mere water under the bridge when faced with the prospect of the dismemberment of the wonderful European Union and the potential unravelling of a greater project to bring all countries within the purview of a one world government. Both appear diametrically opposed to the likes of Boris Johnson and Nigel Farage, but are they? As Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson fell into line with the foreign policy priorities of successive US and UK administrations to push for regime change in Syria and seek confrontation with Russia. While previously critical of the Iraq war and disastrous interventions in Libya and Syria, Nigel Farage has remained loyal to Donald Trump’s presidency.

Could Brexit be a mere charade to engineer the break-up of the United Kingdom?

Reading between the Lines

The Withdrawal Agreement negotiated by British civil servants and EU Bureaucrats under Theresa May’s premiership did little to restore sovereignty to the British electorate. The UK would nominally be outside the EU, but still bound by the rules and regulations of the Customs Union and Single Market, all for a little extra control over labour mobility from EU countries, e.g. not allowing workers to claim in-work benefit until they have paid into the system for at least 5 years. Given the much greater challenge of smart automation displacing millions of monotonous manual and clerical jobs, the native workforce would compete over fewer and fewer entry level jobs. The only way to make a success out of greater economic autonomy would be to invest heavily in STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics), all areas where British students lag behind their Russian, Chinese, Japanese and Indian counterparts. Yet while the public debated the dreaded Northern Irish backstop, that would stop the UK from striking new trade deals independent of the EU until it had definitely resolved the Irish border issue to the EU’s full satisfaction, the UK government was busy agreeing to military unification with the armed forces of other EU members with hardly a murmur of dissent from any of the parties represented in Westminster. The DUP were too obsessed with the constitutional status of Ulster, while the Liberal Democrats and Labour probably welcomed the move. While the military budgets of most continental European countries, with the notable exception of France, have remained subdued over the last 20 years, they have begun to creep up as European military integration became a reality. Germany’s former Minister of Defence and now President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, had the blessing of US-based military strategist, Henry Kissinger for Europe’s remilitarisation. Global strategists owe no special allegiance to their nation states. In the mid to late 20th century it made sense for the superpowers to contain the military ambitions of the main European countries, but with monetary union and only nominal national sovereignty, in the eyes of world chess players, a unified European military command can assume the role of global cop in conflict zones in Africa, the Middle East and most disturbingly of all seek direct confrontation with Russia. One thread that unites most European federalists is their visceral hatred of Vladimir Putin’s Russia, whom they accuse of meddling in European politics, while simultaneously letting American and Chinese tech giants run vast swathes of the continent’s telecommunications infrastructure. In the dying days of her administration Theresa May agreed to let Chinese multinational, Huawei, manage the roll-out of the UK’s controversial 5G network, only a couple of years after the same government let China’s General Power Corporation build new nuclear plants in the UK despite obvious security risks. With the current pace of globalisation it may not matter if the British Isles are whole or only partly in the EU, our lives will be managed by the same corporations.

The Ultimate Con Trick

Many EU-flag-wavers have suggested the true aim of Tory Brexiteers is to hand over British public services to North American big business, which could potentially lead to the privatisation of the revered NHS. There’s only one flaw in this analysis, the neoliberal dream of dynamic private enterprises competing in a regulated free market is on life support. Neoliberalism has outlived its purpose as the main driver of economic growth and technological innovation, as big business no longer needs the services of most working age adults and relies instead on welfare largesse to subsidise its customers. As private healthcare can only serve those able to pay, the global trend is towards public healthcare, not least because local authorities prefer one-size-fits-all social medicine with mandatory vaccinations, mental health screening and regular check-ups for common medical conditions such as diabetes or asthma. In early capitalism, successful enterprises remained largely indifferent to the plight of the great unwashed masses. Today the largest commercial ventures do not want only to satisfy their consumers, but to actively shape their lifestyle and thus to regulate their behaviour. Gay Pride Parades are no longer fringe events of a marginalised minority, they’re sponsored by banks, supermarkets and mobile phone networks with the full blessing of local authorities and the police. New shopping centres bear little semblance to their geographic surroundings with variants of the same ubiquitous brand names and chain stores. Slowly but surely our urban landscape is beginning to resemble a maze of playgrounds with different sets of prefects monitoring puerile plebeians. At the same time countries with proud histories, strong traditions and distinctive cultures have become mere social engineering pilot projects.

UK PLC (the British version of USA Inc.) is so enmeshed with the world economy, that it no longer needs the loyalty of its hapless inhabitants, known affectionately in Germany as Inselaffen (island apes) partly due to their drunken antics in Mediterranean resorts. The business elites only supported the UK’s continued existence to placate remnant patriotism and maintain a tightly integrated military industrial complex.

I seriously doubt whether Boris Johnson, whose family can trace their roots to Germany, Russia and Turkey and who was born in New York city and partly schooled in Brussels, cares more about British self-determination than his pro-EU siblings or the likes of Richard Branson for that matter. They probably care even less about Ulster, the ramifications of Scottish separatism or even the future of the Conservative Party. A no-deal Brexit may not be such a big deal after all for Boris’s corporate friends, but the mainstream media could easily blame Brexit for the looming European financial meltdown as Germany fails to bail out insolvent Italian banks and the London Stock Market crashes. With rising unemployment and a devalued currency, Scotland and Northern Ireland may well vote to leave the UK, conveniently blaming the hated Tories for inevitable cutbacks to public services. That may well be one of the better outcomes. The worst case scenario may be a Yugoslav-style civil war.